Sébastien Doeraene

These days, the JS platform has become an integral part of the language. Yet, until last August, support for Scala.js in Scala 3 was close to nonexistent. A first preview was shipped in Dotty 0.27.0-RC1, with support for the portable subset of Scala and native JS types. Since then, support for non-native JS types was added and will ship as part of Scala 3.0.0-M1. The only missing feature left is JS exports, which we will implement by the next milestone.

What did it take to add Scala.js support in Scala 3? How did we manage to do the necessary work in less than 3 months, whereas Scala.js for Scala 2 took 7 years to mature? Those are questions we aim to explore in this post.

After some background on the architecture of Scala.js for Scala 2, we will cover which components had to be rewritten for Scala 2, and which ones we could reuse. We will see that only a small fraction of the codebase required a rewrite, namely the compiler plugin (weighing about 11% of the total implementation code of Scala.js). Other components like the JDK implementation, the linker and optimizer are reused as is. Last but not least, we could reuse the test suite as well.

This post explores how Scala.js is implemented, and not so much how it is used, although no compiler knowledge is required to enjoy this post. For readers mostly interested on what Scala 3 has to offer to Scala.js users, stay tuned for an upcoming blog post.

Background: the Scala.js architecture

In a simple sbt project, the only difference between a JVM project and a JS project can be as short as this one-liner:

enablePlugins(ScalaJSPlugin)

although for an application with a main method, we will also have

scalaJSUseMainModuleInitializer := true

Two settings, and suddenly run or test will compile the codebase to JavaScript and execute it on a JS engine such as Node.js, with high fidelity compared to Scala/JVM.

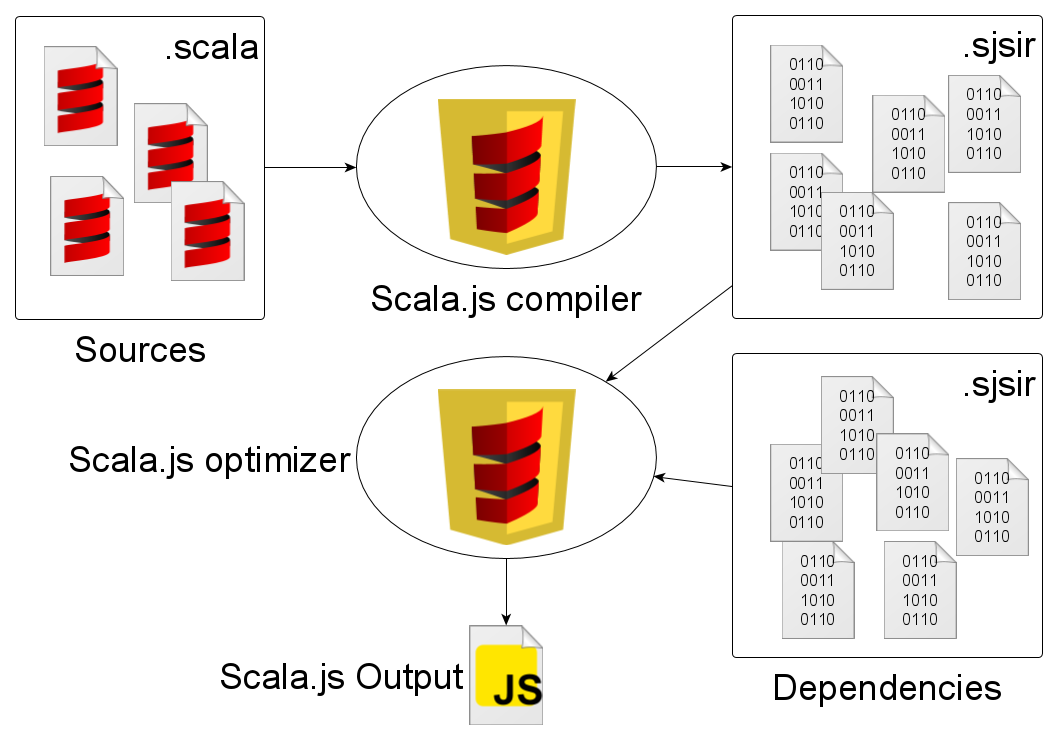

There are many components that contribute to this behavior. Just looking at the compilation pipeline, there are already 4 components involved: the compiler plugin for scalac, the linker, and the artifacts for the Scala standard library and the JDK subset that is implemented.

A compiler plugin

When compiling a Scala.js codebase, the .scala source files are compiled with scalac, augmented with the Scala.js compiler plugin. From scalac, we receive parsing, type checking, elaboration (type inference, implicit resolution, overload resolution, etc.), as well as many transformation phases. The compiler plugin, comparatively to the rest of scalac, is small: it takes the internal compiler ASTs that have been lowered to contain JVM-style classes, interfaces, methods and instructions, and turns them into Scala.js IR (.sjsir files).

Thanks to everything it receives from scalac for free, the Scala.js compiler plugin does not have to deal with a lot of Scala-specific features. Traits have been lowered to interfaces; lazy vals have been desugared; nested classes, defs, and functions have been translated to top-level classes with methods; etc. This is how Scala.js is able to keep up-to-date with all the versions of Scala 2, and be available on the same day as new Scala releases. Not all compile-to-JS languages have that property!

.sjsir files

.sjsir files are similar to .class files, although they are AST-based (instead of stack-machine-based) and contain features dedicated to JavaScript interoperability. The .sjsir format and specification is independent of Scala, its compiler or its standard library. In fact, there is nothing Scala-specific in the entire linker, other than a few optimizations targeted at Scala-like code. This is important because it means that the linker is independent of the version of Scala: we use the same linker irrespective of the version of Scala that was used to create the .sjsir files. In theory, we could even compile other JVM languages like Kotlin or Java to the Scala.js IR, then use our linker to emit JavaScript code. While we have a proof-of-concept for Java, it is nowhere near usable, however.

.sjsir files have binary compatibility guarantees similar to those of .class files. With a few exceptions related to JS interop annotations, if changes to a .class files are binary compatible, then the changes applied to the corresponding .sjsir files are also binary compatible. This allows Scala.js codebases to meaningfully use MiMa to check that they do not break their binary API.

The Scala.js linker (optimizer) takes the .sjsir files from the application and from all the transitive dependencies. In particular, the .sjsir files that are built for the Scala standard library and for the JDK subset. The linker optimizes all of them together, then emits one .js file for the entire codebase.

Aside: What about TASTy?

Inevitably, talking about the Scala.js IR raises questions about TASTy. TASTy has in fact no impact on the implementation of Scala.js for Scala 3; nothing good, nothing bad. And yet:

.sjsirfiles are an intermediate typed AST-based language for compiling Scala code..tastyfiles are an intermediate typed AST-based language for compiling Scala code.

When described as above, one may wonder what is the relationship between the Scala.js IR and TASTy. Could we not just compile from TASTy to JavaScript?

The answer is no, we could not. TASTy has a very different level of abstraction than the Scala.js IR.

| TASTy | Scala.js IR |

|---|---|

| full Scala type system | erased type system (like the JVM) |

| no interoperability knowledge | specific JS interop features |

| complex Scala features (traits, inner/local classes, lazy vals, etc.) | flat classes and interfaces, no fields in interfaces, simple fields in classes, etc. |

During the compilation pipeline, the compiler first type-checks and elaborates Scala source code into a TASTy-level representation (even in Scala 2, although it is not TASTy itself).

Then, a few dozens of phases successively transform that representation to eliminate Scala features and erase the type system.

It is only at the end of that process that Scala/JVM produces .class files while Scala.js produces .sjsir files.

We can compile from TASTy to JavaScript, but that does not take away the fact that we have to perform all those phases again. There is no shortcut. The best way to do that is to reuse the phases that are already implemented in the compiler, of course. From there, we still need to compile the lowered representation of the compiler into JavaScript, and the best way to do that is through the Scala.js IR.

Therefore, from the point of view of implementing Scala.js for Scala 3, the presence or absence of TASTy is irrelevant.

Components of Scala.js core

The components involved here have the following sizes (not counting test files):

The two biggest components, “scalac compiler” and “Scala standard library”, are not part of Scala.js itself. They are reused from the core Scala repository.

Among the components of Scala.js itself, the linker/optimizer and the subset of the JDK are the biggest, and account for 74% of the total. In comparison, the 8,000 lines of code of the Scala.js compiler plugin represent only 11% of the total 69 kLoC.

Add to that about 68,000 lines of testing code, and we get close to 140,000 lines of code for the Scala.js core repository. For fun, we can compare that to the sizes of the repositories for Scala 2 and Scala 3:

It’s worth pointing out that Scala 3 reuses the Scala standard library of Scala 2, so basically those two repositories have the same size.

Supporting Scala.js in Scala 3

Scala 3 has an entirely new compiler codebase, reimplemented from scratch. While many internal concepts such as Trees, Types and Symbols exist in both compilers, their design, semantics, and internal APIs are quite different. The language itself has of course changed a lot as well. What does it mean for Scala.js support?

A replacement for the compiler plugin

Clearly, we had to entirely replace the Scala.js compiler plugin to work with Scala 3. For convenience, we chose to implement the Scala.js support directly inside the Scala 3 compiler (dotc) rather than as an external compiler plugin.

Remember the 8,000 lines of code of the compiler plugin from above? Just like the compiler had been rewritten, we had to rewrite them for dotc. As of this writing, the amount of code related to Scala.js in dotc is about 6,000 lines. They cover virtually everything from the scalac compiler plugin; only JS exports support is missing. The implementation is easier (and shorter) in dotc due to several changes we made earlier in the internal data structures of dotc to make it more friendly to Scala.js.

This is essentially what we have been doing at the Scala Center for the past few months in order to add Scala.js support in Scala 3. As we will see, everything else was already there for us to reuse.

Reusing the linker

We mentioned earlier that the Scala.js linker, written in Scala 2, links .sjsir files independently of the version of Scala that produced them. This is also true for Scala 3! As long as the Scala 3 compiler generates .sjsir files that respect their specification, they can be linked by the existing Scala.js linker published on Maven Central.

Reusing the .sjsir files of the Scala standard library and of the JDK subset

As you may already know, a Scala 3 codebase is able to depend on libraries compiled by Scala 2. This is even exploited down to the standard library level: Scala 3 codebases use the standard library compiled by Scala 2.13. This is possible because the dotc compiler can read the “pickled” signatures in Scala 2 .class files, and it generates .class files that are binary compatible with those produced by Scala 2.

Recall that, if .class files are binary compatible, corresponding .sjsir files are binary compatible as well. Combined with the above properties, it means that Scala 3/JS codebases can reuse libraries compiled by Scala 2/JS. And among them, the Scala standard library and the JDK subset. Therefore, can also reuse the artifacts already published on Maven Central.

That property extends to the JUnit implementation, to the test bridging infrastructure, and even to any 3rd party library!

Reusing the sbt plugin

Without too much detail, the Scala.js sbt plugin has 3 responsibilities:

- Adding the scalajs-library.jar on the classpath of the project and the Scala.js compiler plugin

- Provide tasks to call the linker on the .sjsir files to produce .js files

- Set up

runandtestto use the produced .js file and the testing infrastructure bridge

The last 2 of those responsibilities are independent of the Scala version. They are only concerned with .sjsir files, the linker, and the testing infrastructure, all of which can be reused.

As of v1.3.0, sbt-scalajs implements the first task for Scala 2 only.

sbt-dotty v0.4.2 and later adapts it to Scala 3, so that users need not care about anything.

For example, it removes the Scala 2 compiler plugin that sbt-scalajs adds, and instead adds the compiler flag -scalajs.

When the functionality of sbt-dotty gets merged into sbt itself, sbt-scalajs will be adapted to directly handle the setup of Scala 3.

Thanks to the combination of sbt-scalajs and sbt-dotty, a straightforward build works out of the box with Scala 3 and Scala.js. A small example would be:

// project/plugins.sbt

addSbtPlugin("ch.epfl.lamp" % "sbt-dotty" % "0.4.3")

addSbtPlugin("org.scala-js" % "sbt-scalajs" % "1.3.0")

// build.sbt

ThisBuild / scalaVersion := "0.27.0-RC1"

val myScala3JSProject = project

.enablePlugins(ScalaJSPlugin)

.settings(

// Scala.js project with a main method

scalaJSUseMainModuleInitializer := true,

)

Reusing the tests

While reusing all of the above was definitely a huge time saver (several person·years), it is the reuse of tests that I valued the most during this work. Have you ever dreamed about implementing a significant system from scratch without having to write the tests, because the tests already exist? If yes, you understand what I mean!

In the dotty codebase, we pull the sources of the Scala.js test suite from the scala-js/scala-js repo, and we compile them with dotc with Scala.js support. We then link them and run the tests using the sbt plugin we mentioned above. This ensures that Scala.js in Scala 3 is compliant to all the test cases that we have for Scala 2 (and there are a lot of those).

Of course, we did have to make some changes here:

- Some tests used syntax or other features not available in Scala 3 anymore. As long as using that syntax/feature was not the point of the test, we changed the test in the Scala.js core repo to be compilable with Scala 3.

- Tests that were specifically testing a Scala 2 feature or quirky behavior that does not exist in Scala 3 anymore were moved to a separate directory of Scala 2-only tests. Some of those received Scala 3-specific variants in the dotty repository (for example, reflective calls).

Conclusion

We have explored how the various components of Scala.js fit in the Scala 3 landscape. In particular, we saw that we can reuse most of the hard work that went into Scala.js for Scala 2. We only had to reimplement the compiler plugin, which is comparatively small.